Why Don Quixote is So Misunderstood, Especially as a "Quixotic" Insult

Idealism isn’t the problem, and what Cervantes’ mad knight really teaches us about nostalgia and reality

This is a summary of episode 365 of the Reversing Climate Change podcast. You can listen to it on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you listen to your shows.

🔹 Quick Takeaways

Idealism vs. psychosis: Don Quixote isn’t a cautionary tale against big ideals — he’s a man with a break from reality, acting on bad information.

Written in two parts (1605 & 1615) by Miguel de Cervantes — a comedic, self-aware, and surprisingly modern work from the early 17th century.

Sancho Panza: the grounded sidekick who sees the truth but still gets pulled along by Don Quixote’s charisma.

The danger in nostalgia: Quixote’s fixation on a romanticized, nonexistent medieval chivalry blinds him to the actual world around him.

Not a model for activism: Using “quixotic” to mean “too idealistic” misreads the novel; the real flaw is acting from nostalgia unadapted to reality.

Nostalgia cuts both ways: Political movements left and right invoke golden ages that never really existed.

Living in past or future: Projecting yourself into an imagined past or utopian future can be a way of avoiding engagement with the present.

Takeaway: Ideals are fine—even necessary. Just don’t let them rest on false premises.

📝 Don Quixote and the Misuse of “Quixotic”

Ross Kenyon’s rereading of Don Quixote reveals a gap between how the word quixotic is usually thrown around and what Cervantes actually wrote.

Miguel de Cervantes published the two parts of Don Quixote in 1605 and 1615, making it a contemporary of Shakespeare’s plays. Far from being a solemn warning about the dangers of lofty ideals, it’s a sharp, funny, and self-aware story about a country gentleman so obsessed with medieval tales of chivalry that he decides to live them out—in a Spain that’s already centuries past the age of knights and jousts.

🗡️ The Mad Knight and His Squire

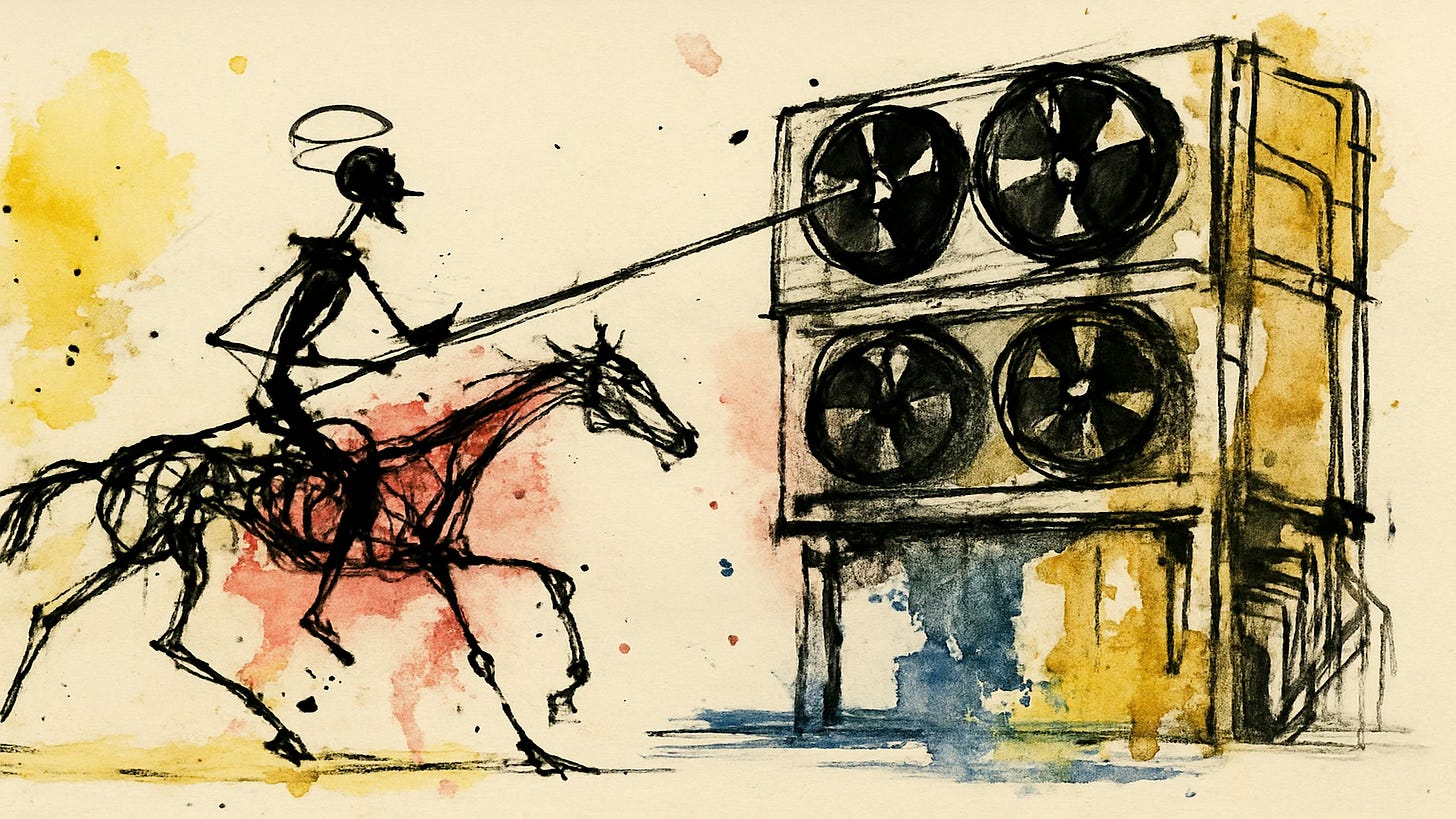

Don Quixote is no harmless dreamer. He’s a man acting on outright delusion: attacking windmills he thinks are giants, charging flocks of sheep he believes are armies, opening lion cages to prove his valor, and “rescuing” convicts who promptly rob him.

Sancho Panza, his peasant squire, understands reality perfectly well, yet still gets pulled along by Quixote’s sheer force of personality. It’s a dynamic as old as politics: clear-eyed followers swept up in the momentum of a charismatic but misguided leader.

🛡️ Not About Idealism — About Bad Premises

Ross pushes back against the casual use of quixotic to mean “overly idealistic.” Quixote’s flaw isn’t having ideals—it’s that his ideals rest on a false picture of reality. He’s not aiming at difficult but worthy goals; he’s swinging at illusions that weren’t great when they existed and are even worse suited for his present moment.

This is especially relevant when critics use quixotic as a jab at reformers or activists. The novel’s real caution is not “don’t try to change the world” but “don’t act on fantasies.”

🕰️ The Politics of Nostalgia

Ross sees Don Quixote as a study in the misuse of nostalgia. Quixote’s devotion to an imagined golden age mirrors how both left and right can romanticize past eras:

Progressives might idealize moments of radical politics or social movements without recalling their limits or failures.

Conservatives might long for a culturally and economically “simpler” time that glosses over exclusion and inequality.

Either way, nostalgia can be a form of escapism, just like Quixote’s retreat into his imagined medieval Spain.

⏳ Escaping Into Past or Future

The tendency isn’t limited to the past. Futurists, transhumanists, and singularity enthusiasts sometimes do the inverse investing identity in a perfect future where pain, scarcity, and mortality are solved. In both cases, the present becomes something to endure rather than engage with productively.

💡 The Real Lesson

If someone calls you “quixotic” for having high ideals, Ross says, don’t take it as an insult as long as those ideals are grounded in reality. Pushing the limits of what’s “realistic” is valuable. Acting on delusions is not.