Why carbon markets need field engineers, not just scientists

By Ross Kenyon

Editor’s note from Rainbow: We’ve long respected Ross and his work in carbon removal. After a couple of interesting conversations about what we’re building, it became clear that his outside view of what we’re trying to do was worth sharing in full. We’re grateful he agreed to write it.

Rainbow didn’t mean to build a registry

Rainbow didn’t want to build a carbon registry. They wanted to build tools for comparative life cycle assessments. But one thing led to another. Life cycle assessments have baselines and project scenarios. To scale them, one needs methodologies. To write good methodologies, one has to understand dozens of different projects. To understand projects, one has to understand how facilities actually run.

And that’s where the Rainbow cofounders realized something: the carbon markets had a field engineering problem.

Registries would develop rigorous methodologies, publish them, and essentially tell project developers: “Here are the requirements. Meet them.” It created walls instead of stairs. Project developers would look at 200-page methodology documents and either hire expensive consultants to translate them, or give up entirely. Some would try to comply on their own and make mistakes that would block them for months or years.

One biochar project registered at Rainbow spent over a year trying to get registered at another registry. They had a unique challenge: decentralized, farm-scale facilities across multiple locations. Not quite artisanal biochar, not quite industrial. The existing processes couldn’t handle the nuance. When they came to Rainbow, they registered them relatively quickly. Not because their standards were lower, but because they could help them navigate the requirements step by step.

The field engineering mindset

I asked Clément Georget, the Rainbow cofounder who leads their field engineering work, to explain the different but complementary roles of scientists and engineers.

“Science builds the foundation of knowledge,” he said. “Engineers take that foundation and make it work in the real world. Scientists map out what we know and what questions remain. Engineers take that knowledge and figure out how to apply it in the real world. On site, in facilities, with real constraints. They operate at different parts of the problem.”

Both mindsets and roles are essential for scaling carbon removal. But they create friction. Scientists might criticize engineers for making decisions without enough data. Engineers might criticize scientists for conducting longitudinal studies when facilities need to operate today. The goal is ultimately to make that friction productive, which is what they’ve done at Rainbow.

The carbon markets desperately need both ways of seeing the world. But I’d argue we’ve under-indexed on the engineering one.

Three tensions that engineering resolves

Tension 1: Precision vs. Practicality

Scientists want perfect data. If they had their way, they’d keep tweaking methodologies until they had complete information. This is admirable—it’s how good science works.

But facilities have to run today. Project developers need to make decisions now. We can’t wait for perfect information to build the world’s largest industry.

Samara Vantil, one of the environmental engineers on Rainbow’s certification team, explained how she handles this: “When we need to make assumptions around data that the project doesn’t have, we conduct sensitivity analysis. How does this assumption affect the outcome? We find good scientific resources to base the assumption on. Then we often add a discount factor because of the uncertainty to ensure we’re not over-crediting, so that we maintain scientific rigor and trust.”

This is the engineering mindset: make conservative assumptions that maintain scientific rigor while allowing projects to move forward. Don’t let perfect be the enemy of merely the very good.

During methodology development, this shows up constantly. Sometimes a data point would improve GHG accounting precision by 0.05%. But collecting it would be prohibitively expensive or practically impossible for facilities to implement. The engineering decision: simplify it. Take the best conservative proxy that is scientifically-grounded. Focus requirements on what actually matters and what facilities can actually provide.

Tension 2: Theory vs. Reality

Samara put it bluntly: “When you are focused on the theoretical, you see boxes on a flow chart. When you have industrial engineering experience, you picture what is happening on site.”

This matters enormously for certification work.

Recently, a project developer built a custom pyrolysis unit with a unique flue-gas cleaning system. The requirements around temperature recording and gas treatment weren’t being met, but it wasn’t clear why or how to fix it.

Samara’s engineering background let her approach it practically: “We could identify the hazards inherent to a pyrolysis process and the controls that should logically be in place. We knew what operating procedures and engineering controls would normally exist, like gas-leak sensors, temperature interlocks, flue-gas treatment stages, and commissioning evidence.”

With that understanding, she could help the developer determine specific changes to equipment and procedures that would meet requirements while remaining financially and operationally feasible. A purely scientific profile might have focused on theory without recognizing the operational challenges, potentially concluding the project wasn’t eligible.

This comes up even in basic compliance work. Understanding environmental risk assessments requires knowing how industrial facilities are actually managed, which documents are normally produced, and what truly happens on site. Samara regularly guides developers: “Here’s what we should expect to see. Here are concrete examples of what you should provide.”

The biochar moisture problem is another example. The methodology might show a simple box: “Sample biochar → Measure carbon content.” But reality is messier. The biochar sits in open storage. Weather happens. Moisture changes. If you don’t understand the actual industrial process, you won’t catch these issues. You won’t know how to fix them.

Tension 3: Requirements vs. Accessibility

Other registries built walls. Rainbow wanted to build stairs.

Clem described the difference: “What we’re trying to build is not a big wall that says ‘Here are the requirements, you have to meet them.’ It’s more like stairs for you to go step by step.”

This requires understanding where project developers actually are. Some have sophisticated tracking systems and environmental engineers on staff. Others are just starting. They might not even know much about carbon credits certification yet. Both need to meet the same ultimate standards, but they need different levels of guidance to get there.

Rainbow spends the necessary time in customer support mode. Developers ask: “Would this tracking system be enough? Should I monitor this additional indicator? How do I set up stakeholder consultation?” They have frequent meetings, give detailed feedback, and help build sampling plans.

One developer told the certification team: “What I like about Rainbow is you don’t leave us alone to figure out everything by ourselves.”

This might sound like hand-holding. But it’s actually how one maintains high standards while keeping the market accessible.

Rainbow is not lowering the bar. They’re helping people reach it.

Can this scale?

The obvious question: “This works when Rainbow is small. Can you maintain this white-glove approach when you’re certifying hundreds of projects?”

Fair question. And it’s one they think about constantly.

Their answer is that having an engineering culture isn’t just about personal attention—it’s about building systems. Everything they’ve learned from hands-on work with projects gets built into their tools, LCA models, and platform.

Rainbow’s certification and science teams work closely with their product team to build features that address real pain points they’ve encountered. They know which requirements cause the most confusion, which data is hardest to collect, where developers tend to get stuck. So they build those solutions into the platform itself.

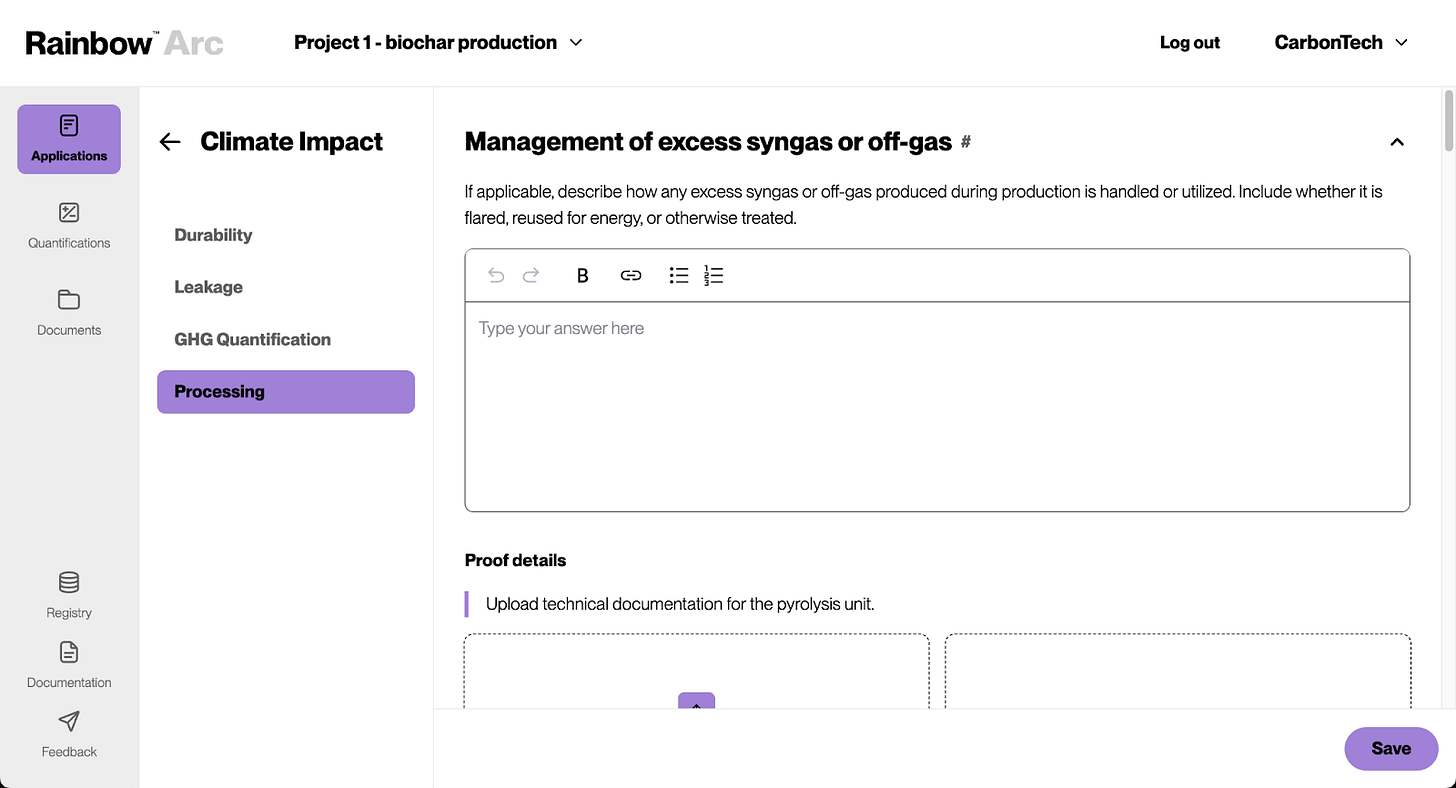

This is how Arc, Rainbow’s certification platform, came to life. It’s customizable to each project’s methodology and unique circumstances, asking only for information that applies to their specific situation. The science and certification teams drove this feature design so developers only see what’s relevant and clear, rather than being overwhelmed by generic and potentially irrelevant questions.

The life cycle assessment is also built into the platform from the start, making calculations fast and transparent. The tools themselves embody the engineering mindset of making things work.

Clem’s team once enabled validation, verification and credit issuance for two biochar projects in just four weeks. That’s not because they worked 100-hour weeks. It’s because they built processes and tools that scaled.

What this actually means for carbon markets

I think the carbon markets have confused scientific rigor with scientific process. They’re not the same thing.

Scientific rigor means maintaining high standards for measurement, verification, and quantification. It means being conservative with uncertainty. It means not issuing credits that aren’t real.

Scientific process means the way scientists actually work—methodically, slowly, wanting complete information before making decisions. This process has to be followed for methodology development, not certification of projects.

Carbon markets need the rigor. But they desperately need engineering process.

This is why registries need field engineers. People who understand how facilities actually run. People who’ve been on site when a million-dollar machine stops working and you need to get it started now. People who can look at a methodology requirement and immediately think: “Can they actually track this? What will the data quality be? Is there a simpler way to get the same rigor?”

Both of the Rainbow engineers I interviewed mentioned the same thing unprompted: they love learning about project processes. They’re genuinely curious about how different technologies work, what makes each facility unique, what challenges each developer faces. That curiosity combined with practical engineering training is what lets them translate requirements into reality.

The market they’re building toward

When the cofounders started Rainbow, their vision was simple: make carbon markets accessible without compromising integrity. Not accessible in the sense of “easier standards” but accessible in the sense of “you can actually navigate this.”

They are an engineering company because their work requires bringing together many different aspects: running projects, developing digital platforms, applying scientific methodologies. One has to make things work together. That’s what engineering is—taking all the tools you have and making them work.

Rainbow reveres science. It is the foundation of everything Rainbow does. When the certification team has doubts about whether evidence meets a requirement, they immediately consult with Rainbow’s science team. When Rainbow is developing methodologies, they do the research. They find the scientific foundations. They make sure requirements maintain integrity.

But then they ask the engineering questions: Is this practically achievable? What will it cost? Can facilities actually track this? What quality of data will we really get? How do we keep the scientific rigor while making it operationally feasible?

That balance—rigor plus practicality—is what carbon markets need to scale. We need credits that are scientifically sound AND projects that can actually get certified. Standards that are rigorous AND accessible. Requirements that maintain integrity AND can be implemented by real facilities in the real world. Scientists that follow the scientific approach to developing methodologies AND field engineers that help project developers navigate the methodologies.

Rainbow stumbled into this by trying to build life cycle assessment tools. And I’m glad that they did. Because somewhere out there, there’s a biochar facility with a moisture problem they don’t know about yet. And they’re going to need an engineer, not just a scientist, to help them figure it out.

Love this! The science-backed registries tend to sound similar, so this is a really interesting distinction.