The Onion of Mercy

On strategic realism, radical Christian pacifism, and why the world needs more forgiveness—even if it makes us look naive.

This is a summary for episode 364 of the Reversing Climate Change podcast.

🔹 Quick Takeaways

Two worldviews in tension: Ross reflects on the pull between strategic realism (assume self-interest, design for defection) and Christian pacifism (radical forgiveness, nonviolence, impractical love).

Realism’s logic: Rooted in both microeconomics and geopolitics, realism assumes states and people pursue self-interest; cooperation only happens when it benefits them.

The Sermon on the Mount: A counterpoint to realism: plain, uncompromising teachings on mercy, forgiveness, and rejecting violence.

The institutional drift: From Jesus’ radical message to Paul’s Epistles, Christianity became more organized and, in Ross’s view, more domesticated.

Stories of uncompromising faith: From Tolstoy’s pacifism to Terrence Malick’s A Hidden Life, examples of people refusing to bend even when it costs them dearly.

Recovering moral clarity: A call to return to simple principles—don’t harm the innocent, end preventable suffering—instead of losing them in tactical trade-offs.

The onion story: From The Brothers Karamazov, a parable about mercy and selfishness; Ross prefers the alternate ending where everyone is pulled from the fire.

Call to action: Move away from guarded realism. Risk naivety. Believe in big, merciful, impractical ideas.

📝 Mercy and the Realist’s Temptation

Ross Kenyon opens “Lowering the Onion into Hell” with a personal reckoning: two worldviews have shaped his thinking, and they could hardly be further apart: strategic realism and Christian pacifism.

Realism assumes people and nations are self-interested actors. In economics, it’s the logic of the prisoner’s dilemma; in geopolitics, it’s the idea that cooperation exists only when it aligns with national interest. It’s tidy, defensible, and persuasive, especially if your goal is to “win” in a competitive, sometimes hostile world.

Christian pacifism, by contrast, is wildly impractical. Rooted in the Sermon on the Mount, it demands turning the other cheek, forgiving endlessly, and resisting evil without violence. It’s the ethic of Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God Is Within You, of the Amish, the Mennonites, and the Quakers.

Where realism rewards caution and tactical thinking, pacifism asks you to throw caution to the wind in the name of love.

📖 From Gospel to Institution

Ross sees a gulf between the gospels’ radical ethic and the organized religion that followed. Paul’s Epistles, full of practical rulings on church disputes, marriage, and leadership, represent Christianity’s shift from anti-institutional fervor to structured community life.

It’s the difference between a monk giving away his cloak to the cold and an abbot trying to keep the monastery solvent. Between Jesus’ unqualified “forgive seventy times seven” and a church that tempers that command for the sake of order.

🎥 Faith That Won’t Bend

Films and biographies offer touchstones for Ross’s vision:

Terrence Malick’s A Hidden Life, about an Austrian farmer martyred for refusing to swear loyalty to Hitler.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X, which critiques Christianity’s historical use to enforce submission among enslaved people.

These stories force uncomfortable questions: What would you sacrifice for uncompromised faith? Is it folly to hold the line when it costs your life, family, or security?

🌱 Recovering Moral Clarity

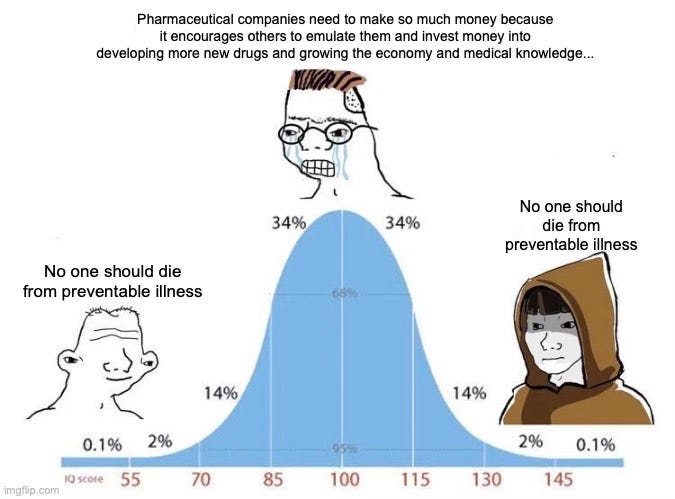

Ross challenges the middle ground where idealists become jaded pragmatists. In that “valley of despair,” tactical trade-offs crowd out moral clarity: we rationalize preventable suffering for the sake of stability, efficiency, or profit.

He argues for returning to first principles:

No one should die of a preventable illness.

The innocent should not be harmed.

Mercy should be abundant, even when it’s “irrational.”

🧅 The Onion

The episode’s title comes from Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, in which a single good deed—giving away an onion—offers a sinful woman a chance at redemption. In Ross’s preferred telling, she accepts help graciously, and everyone clinging to her is pulled from the lake of fire.

It’s a vision of mercy without scarcity; an economy of grace that lifts as many as possible, without gatekeeping who “deserves” it.

❤️ The Fool’s Way

Ross closes with a plea: step back from the seductive logic of realism. Risk being the fool who believes in impractical mercy. Risk naivety in service of something bigger than calculated self-interest.

The world, he argues, has plenty of realists. What it needs more of is “big ideas, big beliefs, big hearts”; the chaotic good of undomesticated Christianity, or whatever your own deepest vision of mercy might be.