How to Live When the Future May Not Be Better Than the Past

My technique for staring into the abyss... and then coming back.

This is a summary post of Reversing Climate Change episode “369: I See a Darkness—The Climate Movement Expects Deep Overshoot”. Listen to it on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts.

This is almost without a doubt the most emotional and also doomerish show I’ve made. Thanks for being along for the ride with me. I hope it makes you think and/or feel.

🔹 Quick Takeaways

From connection to concern: After the warmth and energy of New York Climate Week, Ross Kenyon reflects on the darker undercurrents of conversation. From optimism about carbon removal to fears of climate overshoot, adaptation, and even geoengineering.

Rational pessimism: The rollback of clean energy policy in the U.S. may not stem from denial, but from realism: nations preparing for conflict and self-sufficiency over cooperation.

War and emissions: Great power rivalry could mean climate action stalls while military emissions surge. Guns win over butter.

Adaptation as acceptance: Shifting attention from mitigation and removal to adaptation and global cooling means acknowledging we won’t prevent all harm. We’re preparing for a warmer, harsher world.

The abyss of technology: AI, drones, and automated warfare suggest a near future with less privacy and more mechanized violence; a grim horizon for “progress.”

Moral resilience: When the future darkens, the question becomes personal: What kind of person do you want to be when the world falters?

Integrity over outcomes: Like Alec Guinness in The Bridge on the River Kwai, we risk losing sight of our purpose through small compromises. Integrity, not expedience, must anchor us.

Ghosts and unfinished business: Learning to let go of expectations that your time on Earth may be simple and ever up-and-to-the-right may be the key to living and dying with spiritual strength.

📝 Reflections from New York Climate Week

Ross Kenyon opens this meditation fresh from New York Climate Week, where the energy and camaraderie of the climate community left him both inspired and unsettled. Amid the optimism of carbon removal and technology showcases, a quieter anxiety hums underneath: that overshoot—surpassing safe planetary thresholds—is now accepted as inevitable.

The conversations are shifting from prevention and reversal to adaptation, from optimism to endurance. And the bigger question is no longer whether we can hit 1.5°C, but how we live with ourselves once we know it’ll likely be much worse than that.

⚙️ Rationalizing the Rollback

Rather than attributing the rollback of U.S. clean energy policy to ignorance or cruelty, Ross offers a darker theory: strategic realism. Policymakers, anticipating conflict with China or others, are shoring up domestic energy security—accepting climate deterioration as collateral in a looming era of great-power tension.

This isn’t irrational, he notes. It’s terrifying precisely because it’s rational. “If that’s the case,” he says, “hope for climate progress during a time of great power conflict is extremely limited.”

🌍 From Hope to Adaptation

To focus on adaptation, Ross admits, feels like surrender. Carbon removal and mitigation are optimistic; they imply agency and redemption. Adaptation, by contrast, means we didn’t make it in time. It’s the logic of triage, not transformation. Yet preparing for a hotter, more volatile world is now an unavoidable moral obligation.

Even the field of geoengineering, once fringe, now looms as both a possible rescue and a potential weapon. Solar radiation management could stabilize temperatures, or be used to cripple monsoon systems in a form of climate warfare. When we break the SRM glass in case of emergency, what if we just sit back down in the burning building and wait while also getting soaked? It’s not likely we will use it to buy ourselves more time, but only add to our own suffering.

Unlike carbon removal, which typically cannot harm by design, other interventions carry the shadow of power and dual-use.

🪞 What If You Lose Everything?

In the face of such uncertainty, Ross turns inward. He asks a radical question: If I lost everything: family, wealth, reputation—could I still live and die with dignity?

The exercise isn’t nihilistic; it’s liberating. “When you can make peace with having nothing,” he writes, “you’re also preparing yourself for death.”

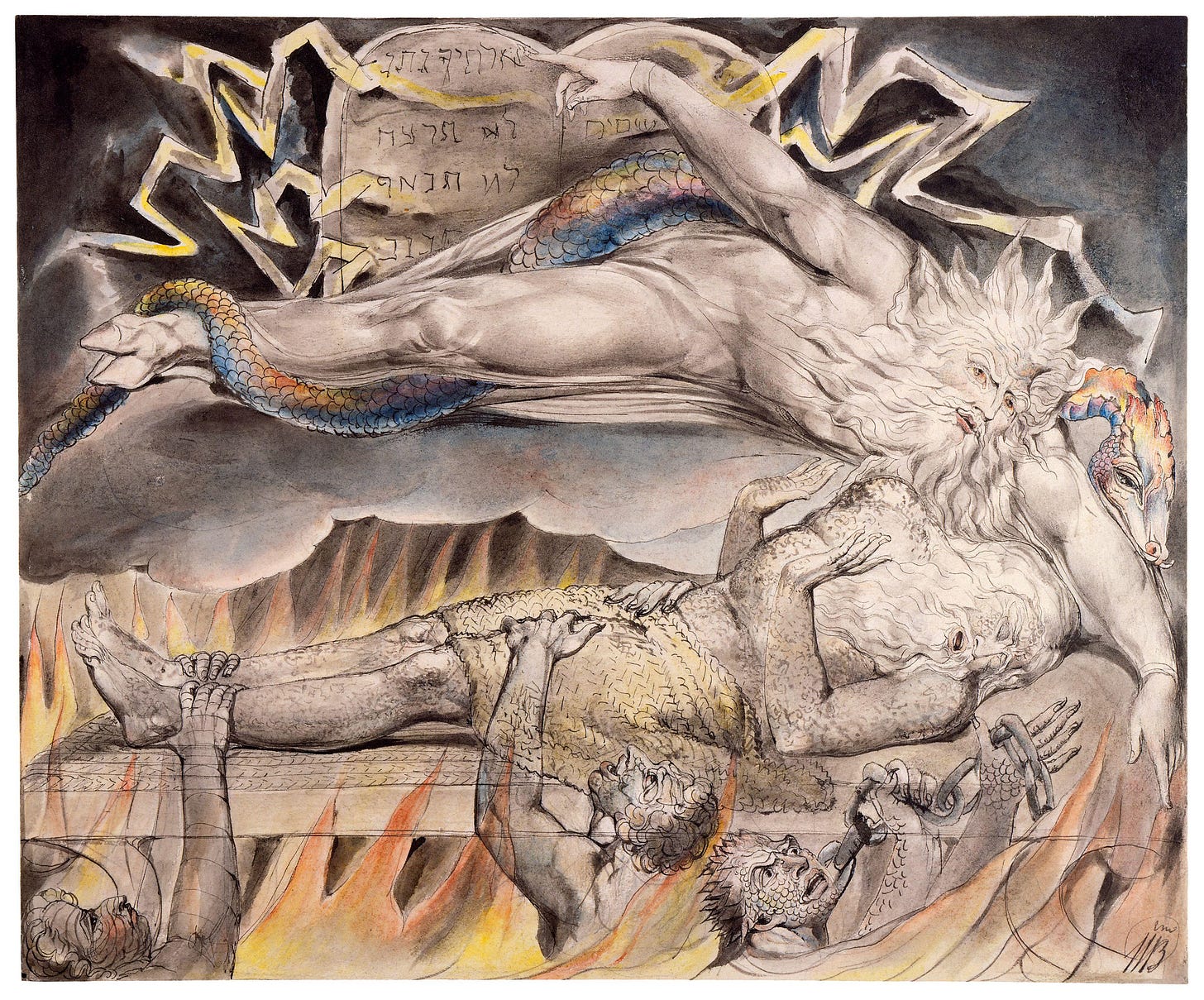

The only thing we can truly control, he reminds us, is the status of our own soul: how lightly we step upon the earth, how kind we are, and what we do when the abyss stares back.

⚰️ Lessons from Eastern Europe

Reflecting on a visit to Lithuania, Ross dives into the history of Eastern Europe, a region once rich with Yiddish civilization and cultural plurality, later annihilated by the twin forces of Nazism and Stalinism. Amid the horror, he finds stories of astonishing courage and integrity: people who chose kindness in the face of certain death.

They remind him and us that character is defined not by comfort but by calamity. “It’s easy to imagine you’d be brave,” he says, “but only the world can test whether that’s true.”

⚖️ Integrity and Compromise

From there, Ross draws a parallel to his own field. In carbon removal, as in all business, integrity faces constant compromise: the tension between science and commerce. It’s easy to rationalize shortcuts as “pragmatism.” But, he warns, small compromises accumulate until you look back, like Alec Guinness’s character in The Bridge on the River Kwai, and ask, My God, what have I done?

Each of us must decide where the line is—and refuse to move it.

👻 Ghosts, Expectations, and Letting Go

Ross ends with a meditation on ghosts. In literature, ghosts linger because of unfinished business—attachments they can’t release. So do we. We haunt ourselves with expectations about the world, our work, our legacy.

Letting go of those expectations, he argues, is not despair but freedom. It allows us to act with integrity even when outcomes are uncertain, to be fully alive even in decline.

🌅 Final Reflection

“Being graceful, loving, and forgiving in this way is the greatest challenge that presents itself to a human on earth.”

The essay closes not with despair but with resolve: a kind of spiritual realism.

The future may not be better than the past, but that doesn’t absolve us from living well. It demands it.