Earth’s Oldest Miners: Microbes

Astrobiologist and CEO Liz Dennett on how microbes could help power the energy transition, why copper might be civilization’s next bottleneck, and what it means to mine responsibly in a warming world

This is a summary of episode 374 of the Reversing Climate Change podcast. It is available in full on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you enjoy your podcasts.

🔹 Quick Takeaways

Microbes as miners: Liz Dennett’s company, Endolith, uses microbial communities to extract more copper from mine waste, turning “bugs into workers” in one of the planet’s oldest industries.

Astrobiology meets geology: With a PhD in astrobiology and roots in Alaska’s geology, Dennett connects planetary science with practical resource extraction; “microbes are the OGs,” she says.

Copper’s quiet crisis: The energy transition needs more copper than all of human history combined. Electric vehicles alone require 5–12× more copper than gas cars.

Why not just recycle? Current recycling systems can’t keep up; supply chains aren’t designed for disassembly. “We throw away half our copper,” she notes. “It’s like ordering takeout and tossing half the meal.”

Evolution, not invention: Endolith uses adaptive laboratory evolution rather than genetic modification, cultivating hardy microbial “mutts” that thrive in the harsh acid and heat of mine leach piles.

Plug-and-play with industry: Instead of reinventing mining, Dennett partners with existing operators like BHP and Rio Tinto to improve yield using microbes; “We meet customers where they are.”

Mining meets ethics: Dennett argues for domestic mining done transparently, with U.S. safety standards, rather than outsourcing extraction to regions with child labor or weak regulation.

The moral tension: She’s candid about working within an industry with a poor reputation, balancing harm reduction with ambition to make it cleaner and safer.

Startup philosophy: Endolith’s culture prizes “safety, critical feedback, and snacks.” Most of the team are women or non-binary, an anomaly in mining, where only 15% of workers are female.

📝 Mining the Microbial Way

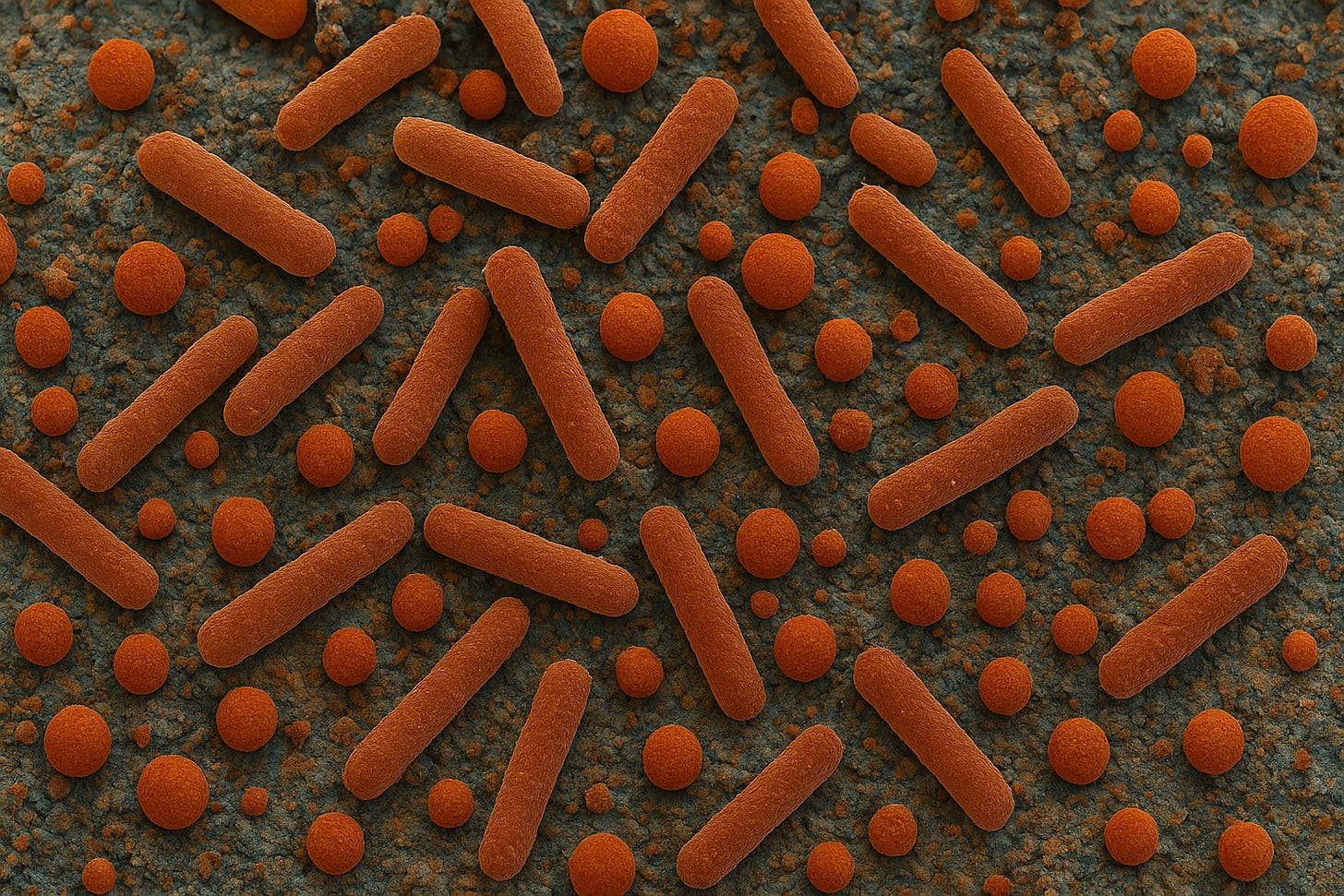

When Ross Kenyon first encounters Liz Dennett, he can’t quite believe her company is real. Microbes that mine copper?It sounds like science fiction. But Dennett, an astrobiologist who once worked for NASA, explains that microbes have been oxidizing and reducing minerals for billions of years. Humanity is just catching up.

Microbes are the planet’s first chemists. They thrive in extreme conditions: heat, acid, pressure, and can “eat” minerals for energy. Endolith harnesses that natural metabolism to pull more copper from low-grade ores and waste rock. Where traditional mining recovers maybe 50% of the copper, microbial enhancement can double yield while reducing waste and chemical use.

It’s a way of making mining less destructive without pretending we can stop mining altogether.

⚙️ The Microbial Revolution

Endolith doesn’t rely on CRISPR or engineered organisms. Instead, it cultivates natural microbial communities through a process called adaptive laboratory evolution. By exposing microbes to progressively harsher conditions: more acid, more arsenic, they evolve traits that let them survive in mine leach environments.

Dennett compares them to dogs: “Engineered microbes are like Labradoodles. They’re great, but fragile. We use the brown mutts from the pound, the ones that can survive anything.”

The company’s approach is pragmatic. Mining is slow to change, so Endolith integrates directly into existing operations rather than trying to replace them. “We’re plug-and-play,” she says.

🧠 The Ethics of Extraction

Ross presses Dennett on the moral paradox: is it right to make extraction more efficient when the goal should be consuming less? She admits the tension but insists it’s better to improve what exists than ignore it. “We need so much copper for electrification,” she says. “If we can get twice as much from the same ore, that’s an obvious win.”

Dennett argues that domestic mining under U.S. regulation is ethically superior to outsourcing to regions with poor labor standards. “It’s harm reduction,” she says. “Yes, in my backyard because that means safety, oversight, and accountability.”

💡 Startup Culture in Hard Hats

Endolith’s internal culture stands out in an industry dominated by men and hierarchy. Over 60% of its team identify as women or non-binary. Their values? “Safety, critical feedback, and snacks.”

Dennett’s candor and color—literally, with her purple hair—are rare in mining circles, but she sees it as an asset.

She calls her microbes “Earth’s oldest miners,” but Endolith’s deeper story is about modern stewardship—using ancient biology to clean up one of humanity’s dirtiest necessities.